"Explain the Business Impact!” (And Other Useless Advice)

Why the standard playbook for tech debt prioritization fails — and what we can do instead.

Ask any engineer and they’ll tell you The Thing that’s slowing them down.

The Thing - whether it’s an overdue refactor, slow build time, outgrown architecture, or a talent bottleneck - is obvious.

But no matter what it is or how painfully obvious, one thing is constant: The Thing doesn’t get done.

Engineers often don’t get the buy-in to do common-sense work.

The value of the work might be obvious to the team, but it’s invisible outside of engineering. Tech leaders get stuck in an infuriating loop; trying desperately to make others see what they see.

As they struggle, this is the kind of advice they get:

Explain the business impact! Show ROI!

Make results visible, fast!

Show industry benchmarks!

Be proactive and try to get ahead of tech debt!

LOL

You might as well tell a business to “grow revenue and lower costs”.

Theoretically and literally correct, but completely useless and impractical.

A typical tech debt project

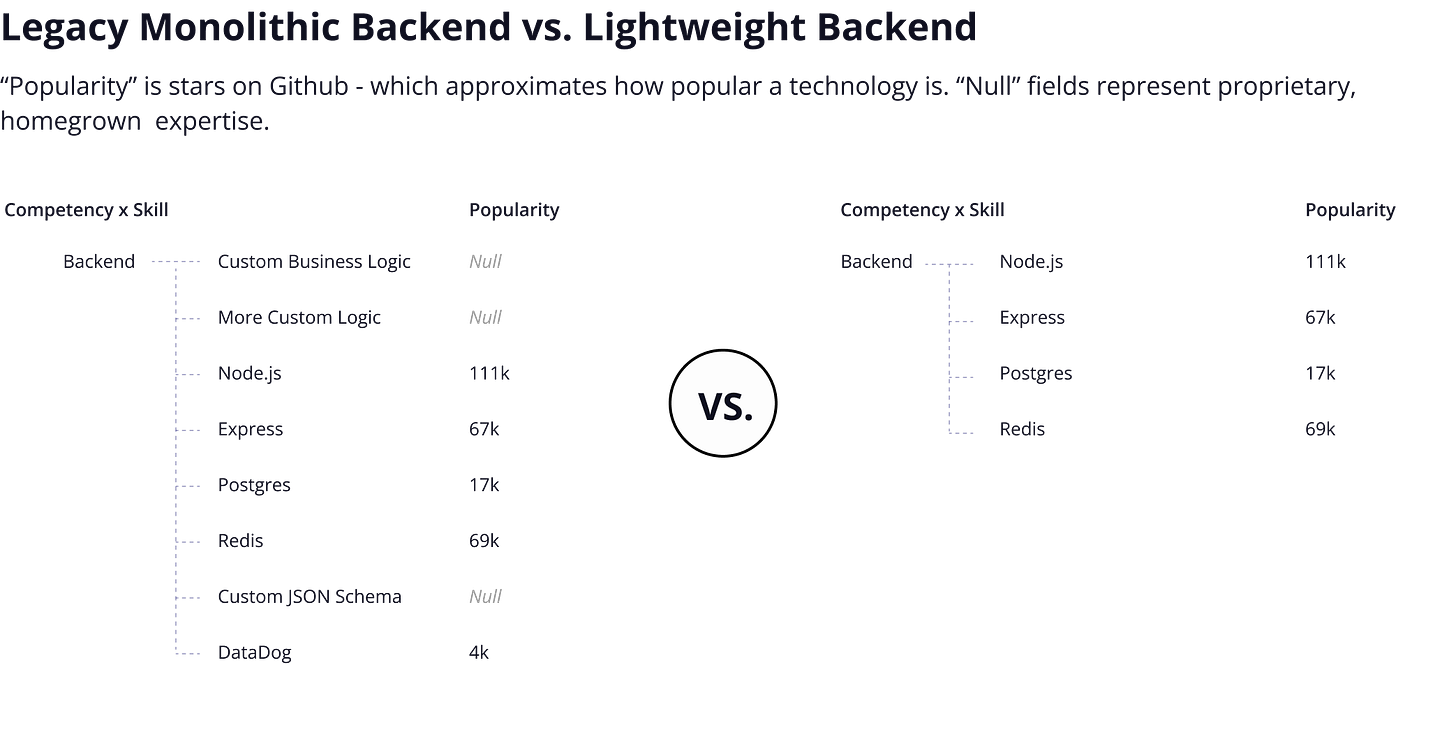

A team is dealing with an unwieldy, legacy monolith. Its acts as a tax on every project- both in terms of LOE and predictability.

What’s worse, it’s unknowable. Knowledge of “C++” or “COBOL” or “PHP” isn’t enough; you need historical context. Ex: it’s been so long that no one remembers why/how the monolith connects to the billing system and ERP in the first place.

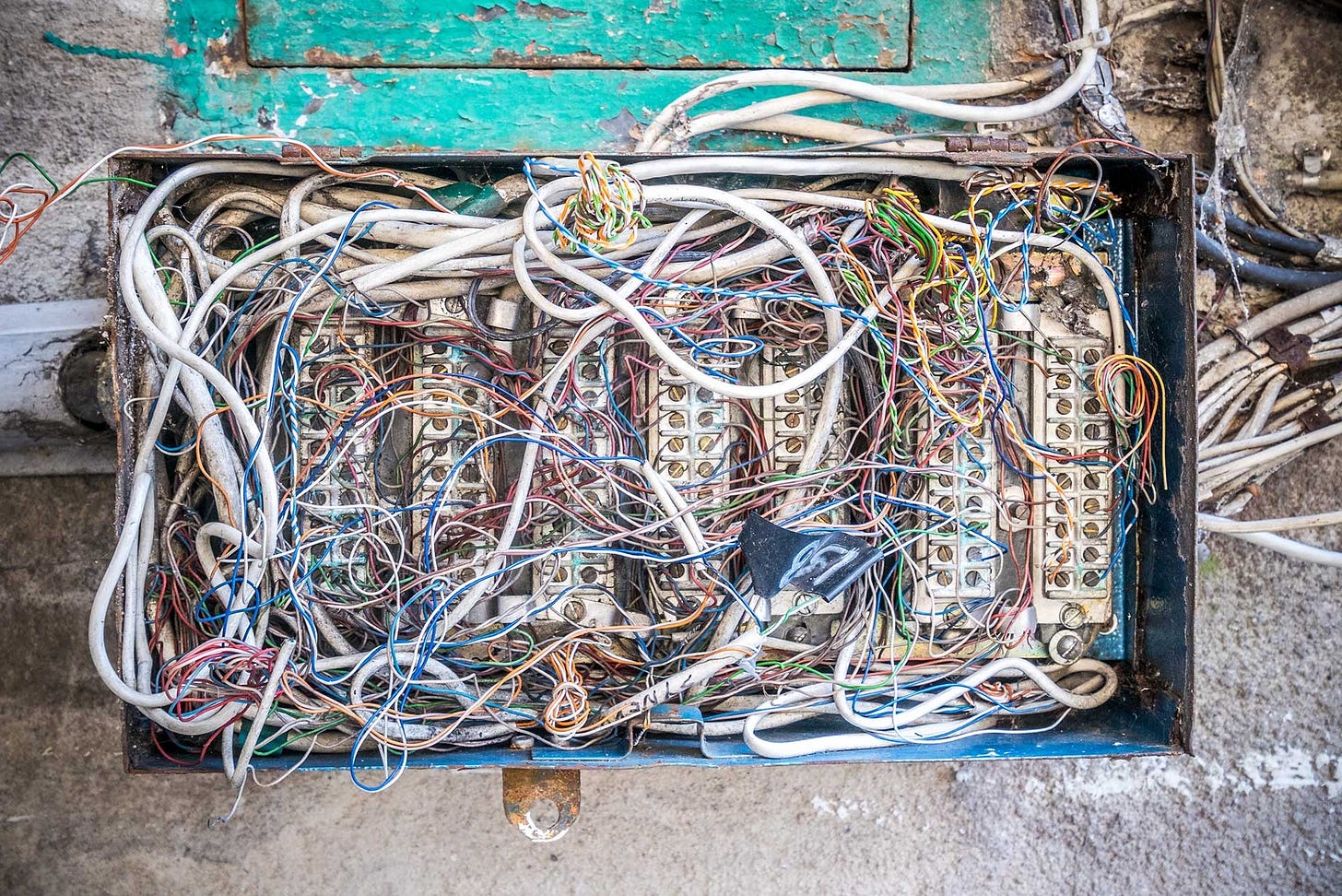

It’s like opening the breaker panel in your basement, and finding an unlabeled, tangled mass of wires.

Oftentimes, the best course of action is to just close the panel, back away slowly, and forget you saw anything. If it’s working and keeps the lights on, don’t start ripping out wires because it “feels messy”.

But…what if you’re rapidly renovating?

What if ConEd is due to upgrade the electric grid?

It’s a (potentially explosive!) millstone around the company’s neck.

Addressing this millstone has obvious impact. But…it doesn’t fit neatly into traditional “ROI” buckets.

There are no “industry benchmarks” because the systems and technologies involved are mired in corporate history and proprietary to the organization. Just scoping the effort could take several weeks.

It might improve long-term engineering efficiency, but…exactly how much is impossible to ascertain. It might de-risk the worst case scenario, but how do you assign a dollar value to not maybe exploding?

Basically, it’s the worst kind of project for traditional project finance. Strategic, complex, ambiguous, and chock full of unknown unknowns.

But still…CTOs and tech leaders are cajoled by the status quo of advice.

They take their gnarly tech debt project and stuff it into a neat framework:

What’s the upfront investment?

What are our milestones?

What’s our ROI?

The entire exercise is mired in politics because this business case doesn’t exist in a vacuum. It’s going to be compared to other initiatives - say, a new feature request to close a seven-figure sales deal.

Our CTO is incentivized to make this business case as appealing as possible.

He shrinks resourcing to make the investment look more palatable. He adds in aggressive milestones and targets to “show progress fast”. He invests hours of research to conjure up an “ROI” that he can sell to his stakeholders.

He does what it takes because he knows this work is needed.

In doing this, he sabotages his team. If the project is green-lit, they’ll need to deliver fairytale gains against unrealistic timelines with a skeleton crew.

But, most times, they won’t get that far. He’s competing with seven-figure sales deals and immediate fires. “Improved resilience and flexibility”, no matter how you spin it, is neither sexy nor urgent.

Especially…when you can just do what you’ve always done: close the panel and look away.

All Too Familiar

If you’re reading this as an engineering leader - you’ve likely lived this.

Seeing - with painful clarity - The Thing that needs to be done

Bending over backwards to explain The Thing

Watching powerlessly as The Thing still doesn’t get done

But…here’s something to consider.

This experience might be endemic within engineering, but it’s almost unimaginable outside of it.

No other function bends over backwards to explain obvious, needed work the way engineering does.

Other functions have their challenges, but they are empowered to tackle obvious issues in a way that engineering is not.

Let’s say…sales were to tell you that their objection-handling playbook had fallen out of date. You can imagine the work of AEs calling up and selling prospects. You’d immediately grasp the implication.

You commiserate. You offer support. You do what you can to help them fix it, fast.

You don’t ask them to stop, drop, and write a fucking business case.

Contrast that with engineering. Most people know that engineers code, but they don’t actually know what coding is like. Case in point:

So when engineers tell other stakeholders that '‘the front-end doesn’t have defined abstraction boundaries”, their cross-functional counterparts just don’t get it.

A soapbox

I’m going to pause and read minds for a minute:

But sales is nothing like engineering!

Engineering is uniquely challenging!

Engineering is complex systems thinking!

This myth is so prevalent, toxic, and unhelpful that it gets it’s own section.

Engineering isn’t a special snowflake.

It’s a knowable, tangible operation.

It’s no more unpredictable than social media marketing. It’s no more complex than compliance. It’s no more strategic & ambiguous than the role of the C-Suite.

But when describe these other teams, we actually talk about their work. Contrast that to how we normally describe engineering:

Story points. Roadmaps. T-Shirt Sizes. Cycle time. Business cases. ROI.

We use byproducts with made-up quantifiers. If we did this with other functions, they would start to look very, very familiar. Imagine:

Marketing trying to champion long-term brand work, when everyone else only sees new leads per week.

A CEO trying to justify an executive assistant, when their board only understands EBITDA.

Lawyers trying to update contracts as regulations change, and being asked for a business case on the “ROI of staying compliant”.

When you lack visibility and measure the wrong things, you can’t see the obvious because you’re completely blind. Too often in engineering, instead of trying to see clearly, we spin in convoluted circles away from the truth.

Visibility into engineering

So how do you create visibility into the work of engineering?

This is where technical accounting can help. Instead of dealing in artificial byproducts, it maps resourcing, architecture, and maintenance.

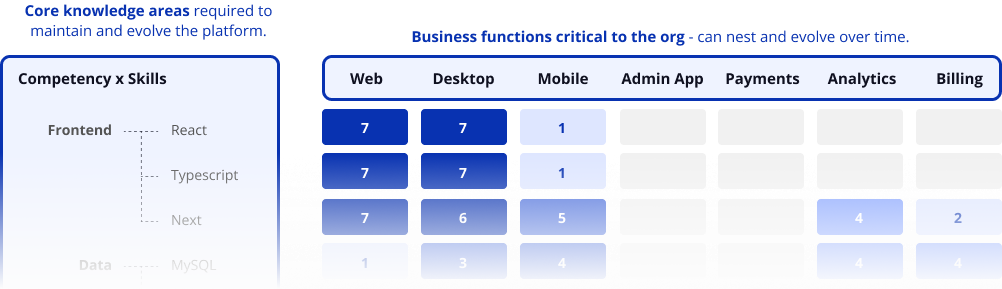

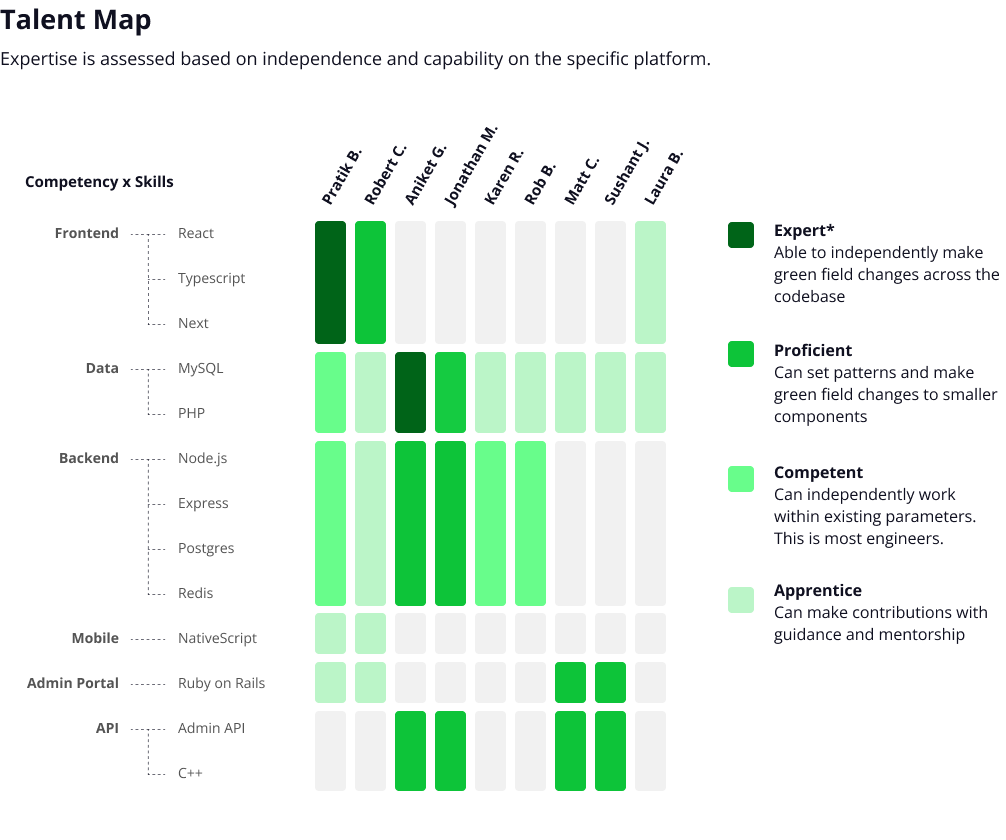

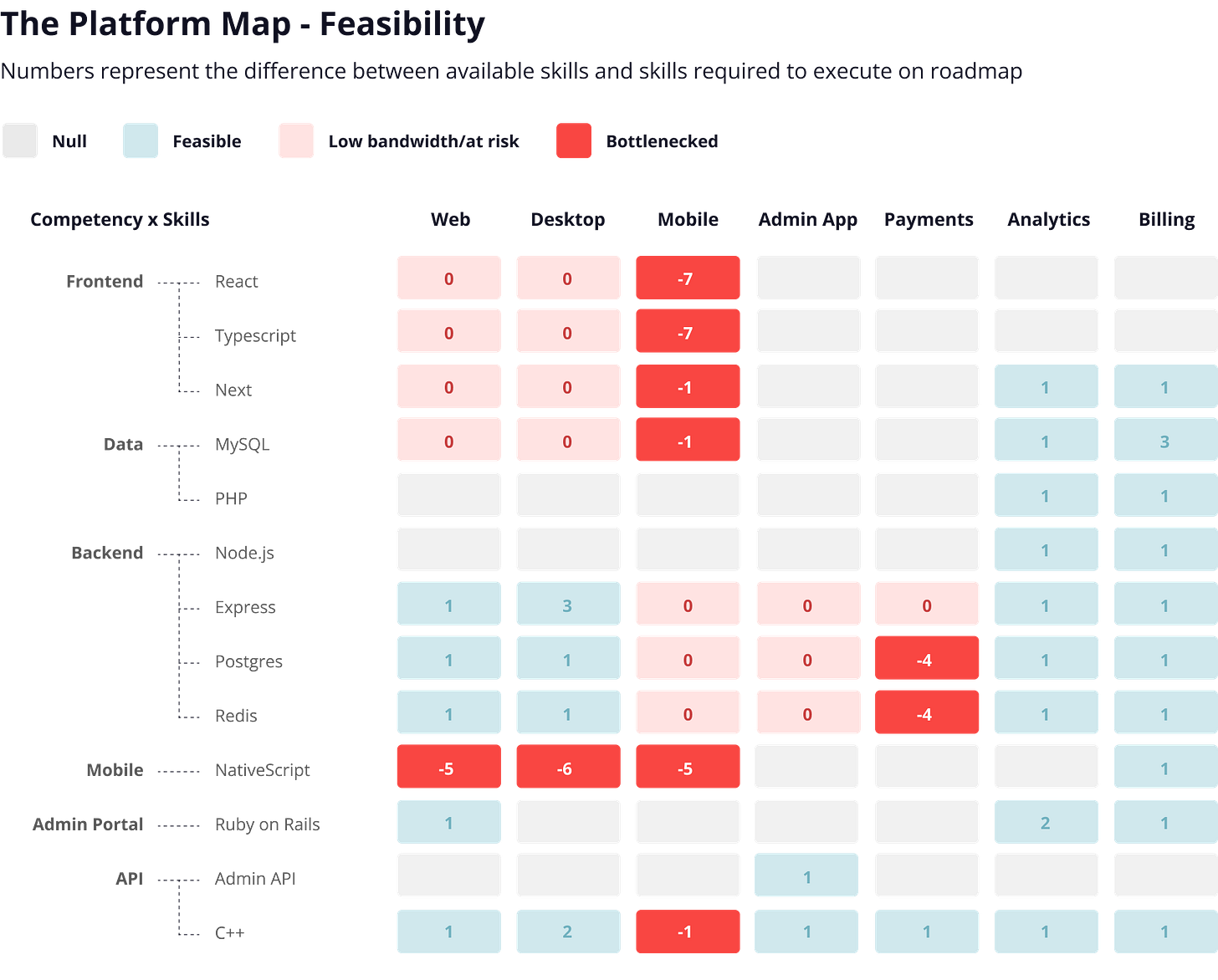

Here’s a typical platform map:

The rows represent different clusters of knowledge required to maintain and evolve the platform. The columns represent core business functions.

The colored intersections represent the number of ICs who can work on any given part of the platform.

This view is constructed by surveying and understanding the capabilities of the existing team relative to relevant parts of the platform, right now. Ex: we don’t care whether or not someone “is good at frontend” - we care that they know the frontend relative to the platform in question.

This way of mapping engineering surfaces what’s often invisible:

Maintenance: keeping evolving systems alive outside of new features

Architecture: how evolving patterns and technologies shape how engineers think and build

Resourcing: who holds the required knowledge to maintain and evolve these systems at all

In doing so, it makes The Thing visible - and obvious - to everyone else. Take these examples:

Every one of these scenarios can derail your success. Sometimes, they kill entire companies.

It’s why engineering leaders are so desperate to address them - they see a clear and present threat.

They fail because they end up tackling these existential threats alone. Even when they’re successful against all odds, they get no applause. The problem - and the massive effort required to fix it - is invisible.

But when we bridge the visibility gap, everything changes.

Everyone can see The Thing.

No convoluted questions are asked: everyone innately gets it.

They all band together to help.

When things get done, they celebrate as a team.

In hindsight, it all seems so simple.

After all - isn’t this just how you get anything done?

Christine Miao is the creator of technical accounting–the practice of tracking engineering maintenance, resourcing, and architecture.

It turns massive initiatives - like breaking up monoliths, complex refactors, or cleaning up tech debt - into visual reports simple enough to explain to your grandmother.

In doing so, it makes engineering work visible - and what’s essential, obvious.

I sometimes wonder if the communication problem is a catch-22. Do engineers need to over explain themselves because they more often than not lack the skills to communicate effectively, or have they given up trying to explain things well because they always have to justify and over explain?